Fairhope Days

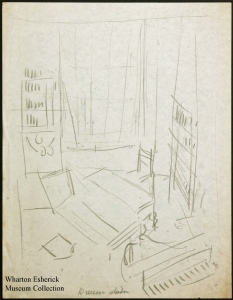

Wharton Esherick in Fairhope, 1919. Esherick Family Photo Albums

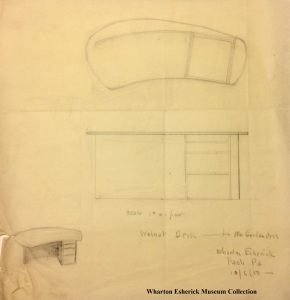

Fairhope, Alabama sits high upon the bluffs overlooking Mobile Bay – or as the first Spanish explorers called it: la Bahia de Spirito Sancto or “the Bay of the Holy Spirit” for its breathtaking views and peaceful serenity. Fairhope has a long history of attracting artists, writers, and craftspeople going back to its founding as a single tax colony in 1894. It was Letty Esherick’s interest in progressive education that brought the Eshericks to Fairhope for their first visit in 1919; drawn by Marietta Johnson and her School for Organic Education. Fairhope proved to be a life-changing experience for Esherick, who was struggling to find his artistic voice at the time of their trip. It was in Fairhope that Esherick picked up his first set of woodcarving tools and explored a new medium that would lead to his artistic legacy.

A Fair Hope of Success

The idea of Fairhope emerged in Des Moines, Iowa in the 1890s when a group of Henry George admirers began meeting to discuss his principles of a single tax community. The group’s leader Ernest B. Gaston felt that George’s philosophy deserved the chance to be tested. George’s plan proposed a community where only the land was taxed, which he believed, and Gaston agreed, would stimulate economic growth. Gaston was deeply upset with social conditions at the end of the 19th century and saw the single tax theory as a way to even the playing field.

Cottages in Fairhope

The group became the “Fairhope Industrial Association of Iowa,” deriving their name from a statement made that their experiment had a “fair hope of success.” In 1894 they established their colony and in 1904 they were officially incorporated. Membership to the colony cost $100 a year, and members were leased land on a 99-year renewable lease in which lessees would own whatever improvements made to the land including the construction of houses and other establishments. The colony’s “member’s only” model would only last four years.

By 1908, the Fairhope Industrial Association realized that in order to continue as a community, they had to open themselves up to non-members as lessees. As a result, the city of Fairhope was formed as a separate entity and formal municipality. Gaston had hoped that people who moved to the city of Fairhope would all choose to join the movement once they saw the benefits of the single tax community nearby, but they rarely did.

Letty

Letty had long been interested in the progressive education movement happening at the start of the 20th century and dreamed of opening her own school one day at the Esherick homestead, Sunekrest. She and Wharton attended a speaking engagement in Philadelphia that featured Marietta Johnson, a leader in the progressive education movement and founder of the Organic School in Fairhope. During Marietta’s speech, Letty hung on every word, and not long after she and Wharton decided to leave for Alabama where their 3-year-old daughter Mary could attend the Organic School, and Letty could volunteer and study under Marietta.

Today the Bell Building that stands on the original campus of the Organic School is now home to the Marietta Johnson Museum. Photo by WEM docent Bob Zrebeic.

Marietta Johnson’s educational philosophy hearkened back to the days before public schools, believing education should be as organic as children learning from their surroundings through experience. The curriculum at the Organic School incorporated traditional academic studies with handcrafts, music, singing, folk dancing and wholesome play in the fresh air. Marietta believed that arts were natural and elemental to children and that knowledge of practical arts, such as woodworking and pottery, might actually help children later in life as they’d need to provide for themselves. Over the course of the Esherick’s two visits, all three of the Esherick children attended The Organic School.

Wharton

While Wharton spent much of his time in Fairhope traversing the countryside sketching and painting, he also found himself involved at the Organic School. When he voiced criticism of how art was being taught at the school, Marietta challenged him by asking what he was going to do about it – so he became an art teacher. He chose to teach in the afternoons, so he could save the best part of the day, the morning, for himself. He also met author Sherwood Anderson, best known for his work Winesburg, Ohio, and the two formed a friendship that would last through Anderson’s death in 1941.

Though Fairhope was a progressive community, segregation still affected Fairhope’s African American population. Esherick and Anderson were both highly interested in the African American culture and often attended services at their church. Not long after he started teaching at the Organic School, Esherick also became an art teacher at the black school, which the white residents of Fairhope did not like. A lawyer warned Wharton about what the townspeople would do:

“‘Mr. Esherick,’ he says, ‘You’re going to be chased out of town.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘The people are very much disturbed at you. They know you’re going out and teaching at that colored school and they don’t like it. … When you’re away they will come here and they’ll gather all the things in your house and put them on the wharf there and kick you out of town.”

Esherick ignored the lawyer’s warning and instead chose to walk two miles out of his way so that the locals would not know he was headed to the black community. At the end of the school year, Esherick held an exhibition of his paintings at the Organic School and invited his students from the black school to attend and see their instructor’s work. This caused a major uproar in Fairhope, but Marietta stood by Esherick and allowed everyone to enjoy his paintings which featured the beautiful carved wooden frames he had made at the Organic School.

The Painter Becomes a Printer and a Sculptor

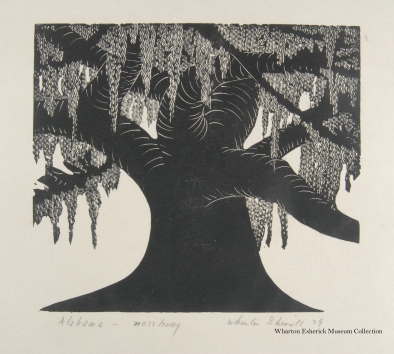

Alabama – Moss Hung, 1929 Woodcut by Wharton Ehserick

It was Marietta Johnson who suggested Wharton explore woodcarving while he was at the Organic School. To compliment his oil paintings, he carved elaborate wooden frames which often reflected the subject of the painting within. The frames were a big hit and Wharton discovered a medium which he greatly enjoyed.

He began exploring printmaking, turning many of his sketches of Fairhope’s trees into block prints like the ones seen here. In Fairhope, he met author Mary Marcy, who asked him to illustrate a book of poetry she was writing. He chose to do so with woodcuts. Marcy would send Esherick one of her poems, he’d carve the block and send her a print and they continued back and forth until the book was finished. Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk was published in 1922 featuring 78 of the 100 woodblocks Esherick created for the publication.

During the Esherick’s second visit in 1929-1930, Esherick met potter Peter McAdam. McAdam worked at O’Neal Pottery in nearby Daphne and became known throughout southern Alabama for his creative ceramic work – especially his face jugs, monkey jugs and other ceramic novelties. He is noted as being the most artistic of all the potters in the area and while others made purely utilitarian pieces, McAdam’s work always had great artistic flair. It’s easy to see why he and Esherick got on well. It was at O’Neal Pottery that Esherick and McAdam made a series of ceramic animals which Esherick brought back to Paoli to install as yard ornaments or sell to clients. The two also created several dishes for the Esherick family including redware dinner plates with a pelican carved into the surface, and several colorful bowls and dessert plates.

Dishes by Esherick & McAdam

More on Fairhope

Want to learn more about Fairhope? Fairhope Days, an exhibit that takes a close look at the Esherick’s time in Fairhope and features some rarely seen artifacts from their time there is on display in the Museum’s Visitor Center gallery through September 2nd. Highlights of the show include a handmade travel chess set Esherick made at the Organic School, a Fairhope-era oil painting in an elaborately carved frame Esherick crafted there, as well as two ceramic animals – an elephant and a pelican – made by Esherick and McAdam at his pottery in Daphne.

On July 8, the Museum will host wood artist and Esherick scholar Mark Sfirri for an Exhibit Talk at 2pm! Mark has been studying and researching Wharton Esherick since 2006 and has since authored six articles on Esherick and his work. In conjunction with our summer exhibit Fairhope Days, Mark will discuss Fairhope’s founding and history as well as Marietta Johnson and her School for Organic Education, the impetus for the Esherick’s initial journey south. Admission to the Exhibit Talk is free, admission for a self-guided tour of the Studio, open from 1 to 4 p.m., is $12 for adults and $6 for children ages 5-12.

Post written by Curator & Program Director, Laura Heemer.

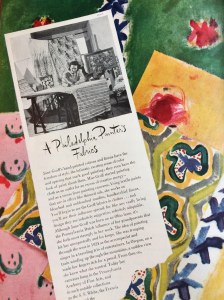

Bold and playful, this textile design by June Groff was acquired by Jack Lenor Larsen, Inc. as “Spice Garden.”

Wharton Esherick’s work is often described as having integrity, and an honesty that cuts through any art jargon one might try to apply. As his nephew, the architect Joseph Esherick put it, “In his work [Esherick] spoke as an individual, but not in a private language, with the result that he and his work speak to everyone.” One could make a similar claim, and some have, about the work of artist and textile designer June Groff. Her hand-painted and printed fabrics were “done with a dash,” as Barbara Barnes put it in a 1949 Philadelphia Bulletin, ”and with complete absence of artiness or affectation.” Like Esherick, Groff seamlessly merged the skills of academic training with the world of everyday objects. The result? Work that sings unselfconsciously with the pure, joyous energy of creating.

Born in Ohio, June Groff (1903-1974) was a Pennsylvania Dutch farm girl who later found great inspiration in returning to her childhood memories of barnyard animals, red schoolhouses and country scenes in her work. She would later recall admiring her sister’s watercolors as a child, but would not realize herself as an artist until much later. Her life took a more meandering path and her initial studies were in music and dramatics. For several years she traveled the west as an accompanist and singer, one in a trio of entertainers, when in 1924 she was struck by the inspiration to paint. By Groff’s own recollection, “It was an Oregon mountainside, with fuzzy dark spruces poking their heads up through blankets of snow that made me want to paint. Studying art became my dream from then on, but it was several years before I could afford the art studies.” When she did finally begin her training she worked prolifically and aptly in many mediums, including oil paintings, watercolors, embroidered “needle paintings,” stained glass and hand-painted and hand-printed fabrics (and poetry too!)

Groff’s first art courses were at New York University (1928-1929), followed by five years at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts including a Cresson Scholarship to study and travel throughout Europe. Upon returning, she spent two years studying at the Barnes Foundation, and within a year had a piece on display in second half the New York World’s Fair in 1940 in (you guessed it Esherick fans) the Pennsylvania Hillhouse exhibit. This interior domestic display well-known to Esherick fans was designed in part by architect George Howe and included primarily Esherick furnishings from his celebrated spiral staircase to the world’s fair table and chairs. Sprinkled among the furnishings was Groff’s Bull Over Spain, a decorative yarn panel hung on the wall.

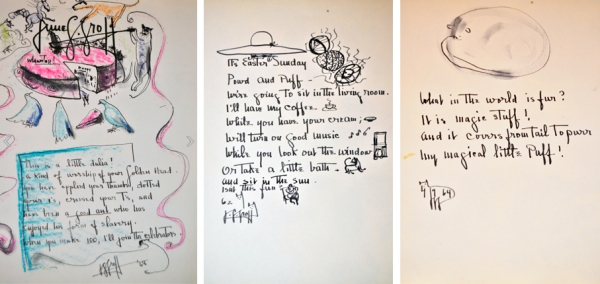

It’s hard to know when June Groff and Wharton Esherick first met. They would come to show together many times over the years, but surely this exhibit would have put them in touch. As two artist living and working around Philadelphia, their lives overlapped in other ways, too. One of Groff’s good friends, Bess Hurwitz and her husband Nathan, were also Esherick’s friends and collectors (buying his Five-Sided Table from the World’s Fair when no one else would). Groff was a driven and independent spirit; it’s easy to imagine she and Wharton getting on well together. In one letter to Wharton, apparently after a visit to his studio, June begins (in her exuberant handwriting): “My Dear Wharton, Old Dear – it was just plain good for my soul to be out there last nite … I am very fond of you all – and appreciate you all for so much you are,” going on to insist he visit her to see her new designs, and thanking him emphatically for delicious popcorn and peaches from the previous evening.

Esherick owned several fabrics designed by Groff, a few of which are seen regularly by visitors to the Studio. Two pillows made with her fabrics rest on the Bok sofa in his bedroom, one a printed motif of continuous trees, the other a heavier fabric with a basketweave design of loose blue and green brushstrokes. It is likely the colors have worn away considerably on this basketweave design, as decades ago this fabric covered Esherick’s rail sofa across from the fireplace downstairs. After so much use the sofa was reupholstered with the blue cover seen now, but not before saving a section for a pillow.

In the dining room, another pillow of Groff fabric is on display, featuring large, loose and confident oval brushstrokes with hints of turquoise and faint pink. On the wall behind the bench where the pillow sits (a favorite spot of Esherick’s) a June Groff oil painting entitled Horseplay shows her fauvist color palette which favored vivid over representational hues.

Our Museum collection also includes yardage of Groff’s kept in storage including two variations of a printed design that would eventually be acquired by Jack Lenor Larsen. Larsen later recalled Spice Garden, as it was named, as being one of the first printed fabrics sold by his company and an extremely successful one at that. Drawing inspiration from nature, this design combines her signature bold, energetic brushstrokes with a masterful sense of color and visual balance. The seemingly scattered pattern (depicting flowers, birds, and butterflies) is held together by a lively visual rhythm of complimentary colors – her vibrant personality coming through with each mark. Over the years Spice Garden was produced in a variety of palettes and materials, including pastel hues on velvet, also in our collection.

June Groff textiles were highly sought after in the 1940’s and 50’s. What began as a singular artist’s studio grew to as many as 30 employees working to produce around 1,000 yards a day from her Philadelphia factory. She sold fabrics to major fashion designers like Hattie Carnegie and Clare Potter and had work featured in Harper’s Bazaar and Paris Vogue. Her work, both textiles and paintings, were collected by major institutions including the Philadelphia Museum of Art (who has her exuberant “Spice Garden” fabric currently on view in their current Modern Times exhibit), the Barnes Foundation, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts as well as private collectors like Emile Gauguin, Francis Biddle, and Vera and Samuel White.

Yet somehow, June Groff managed to fall into obscurity in the later years of her life. She passed away in 1974, and despite the acclaim, she reached in her own lifetime, had come to be somewhat of a recluse in her Philadelphia home, shared with 10 cats and 90 pigeons. Her name seems to be bubbling to the surface again in more recent years, with textiles going on display in Philly restaurants several years ago, or her recent inclusion in the PMA’s Modern Times exhibition, and we can only hope for more. It’s a curious thing, who is remembered and who is forgotten from the history books. June Groff’s role in the Philadelphia art world and beyond should not be forgotten – her quick gestures on fabric, too joyful and genuine to be pretentious, are just one aspect of her work, leaving paintings, embroidery, stained glass and more to be rediscovered. Time and art keep marching forward and we should certainly bring June Groff, her work, and her instantiable energy to create along with us!

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

This early woodcut by Wharton Eshrick illustrated the poem, “Ornaments,” in “Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk,” 1922.

Wharton Esherick’s adventures in printmaking began in the winter of 1919-1920 when he befriended author and social activist Mary Marcy. At the time, Wharton and his family had traveled to Fairhope, Alabama, a single-tax community, full of progressive thinkers, artists and authors. It was there he was given his first set of wood carving tools, carving frames for his paintings and experimenting with woodcuts. Soon Esherick and Marcy were working together on a children’s book on evolution, Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk. Continuing a theme from an earlier book, Stories of the Cave People, Marcy began writing playful verse about everything from prehistoric pony rides to the Mesozoic roars of dinosaurs.

Illustrating the book are some of Esherick’s earliest woodcuts, rudimentary but well composed, created hand in hand with the text. When Marcy began the project she shared a poem with Esherick, who was inspired to create a woodcut illustrating the poem. Inspired by his woodcut Marcy wrote another poem, shared it with Esherick who carved another woodcut. In this way, they collaborated until Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk was complete.

Printmaking became a critical transitional medium for Esherick, providing him with some of his first public acclaim, including from Carl Zigrosser, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, who became a frequent visitor to Esherick’s studio. Esherick would go on to illustrate a number of other publications through the Centaur Press and have his woodcuts published in celebrated magazines of his day including Vanity Fair, Century, and The Forum.

Recognizing the important role printmaking played in Esherick’s development as an artist, the Museum has hosted an annual printmaking competition for high school since 2010, thanks to funding and support from an anonymous donor. What began with just a handful of local high schools has now expanded to include Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia counties. High school classes submit their best work, and from that, a jury of staff and art professionals select finalists to be exhibited here at the Museum.

Imprint 2018, currently on view in our Visitor Center, is unique in that we selected a second round of finalists who, along with those in our show, will be included in an exhibition at the Philadelphia International Airport in 2019. The exhibition at the airport will include an introduction to Wharton Esherick and WEM and hopefully excite the curiosity of a few travelers passing through! In anticipation of this partnership with Art at the Airport, we introduced a theme to this year’s competition: The Life and Work of Wharton Esherick. The results astounded us, with students exploring a range of interpretations, including portraiture, landscapes and places Wharton loved, and depictions of the Studio both real and imagined.

Featured here are the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place winners from this year’s show:

Left: 1st Place winner “Cheeter and Jeeter Movement” by Angelina Calderone, Abington Senior High School, Right: “Jeeter” 1934, Wharton Esherick.

Artist’s Statement: I did this piece because I very much enjoyed his horse sculptures and they inspired me since I read about how happy these sculptures made the community.

Curator’s Note: In 1934, Esherick sculptured two horses to stand out front of the Hedgerow Theatre in Media. Cheeter and Jeeter were carved out of pine and often a favorite “play ground” for children at the local School of Rose Valley who enjoyed climbing all over them.

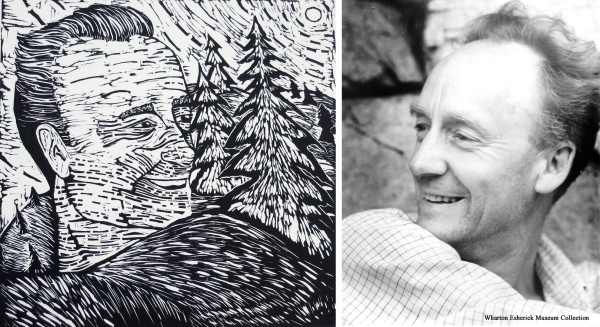

Left: 2nd Place winner “Homage to Wharton” by Katherine Flad Abington Senior High School, Right: Wharton Esherick c. 1930. Photo attributed to Consuelo Kanaga.

Artist’s Statement: Homage to Wharton is inspired by the life and excitement Wharton Esherick had throughout his life. The wooded scene behind him is meant to slowly morph into his shoulder representing the effect the Pennsylvania woods had on Wharton Esherick and his work.

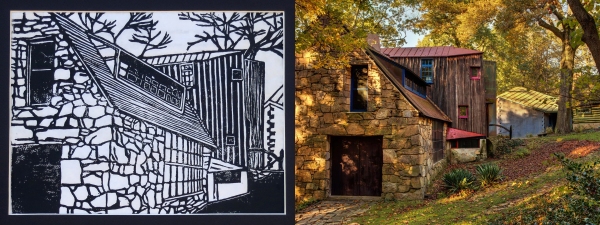

Left: 3rd Place winner “Wharton Esherick Museum” by Adeline Cambria, Bishop Shanahan High School, Right: Photo of the Museum by Charles Uniatowski.

Artist’s Statement: On the topic of Wharton Esherick’s life I knew that I wanted to focus on architecture. Architecture is a huge passion of mine and after seeing Wharton Esherick’s Museum I was completely inspired.

Imprint 2018 is on view in our Visitor Center now through May 20.

More on the competition can be found here.

Post written by Communications and Special Programs Manager, Katie Wynne.

Women’s History Month Spotlight: Ruth Esherick Bascom

March is Women’s History Month, and while there have been many amazing women involved in Esherick’s life and the history of the Museum, one that truly stands out is Ruth Esherick Bascom. Ruth, Wharton’s second daughter, was born at the Esherick farmhouse, Sunekrest, on June 28, 1922 where the walls of her childhood bedroom were covered in murals of barnyard animals painted by her father.

March is Women’s History Month, and while there have been many amazing women involved in Esherick’s life and the history of the Museum, one that truly stands out is Ruth Esherick Bascom. Ruth, Wharton’s second daughter, was born at the Esherick farmhouse, Sunekrest, on June 28, 1922 where the walls of her childhood bedroom were covered in murals of barnyard animals painted by her father.

Ruth’s upbringing was far from traditional. Her mother Letty was interested in progressive education and longed to open up a school of her own at Sunekrest where she could educate her children and open it up to local children as well. Before Ruth was born, Letty, Wharton and their first daughter Mary spent the school year of 1919-1920 in Fairhope, Alabama at the School for Organic Education. Letty greatly admired Marietta Johnson, the school’s founder. Though Letty thoroughly studied the progressive education movement, she was never able to realize the dream of her own school. When it was time for Ruth to start school in 1928, she joined her sister at the Hessian Hills School at Croton-on-Hudson, New York; a progressive school that believed in combining study, work, play and living to teach children. You can watch a great short documentary about the Hessian Hill School here.

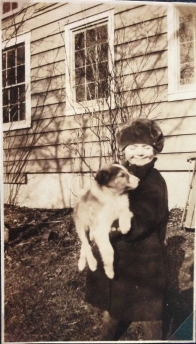

Ruth and her pup, 1920s

In order to pay for the two girl’s tuition, Letty accepted a position as housemother for the dormitory where she cooked and cared for the borders. However, one day she was found lying comatose on the kitchen floor, suffering from encephalitis and had to leave her position to recover. Mary and Ruth had to leave the Hessian Hills School.

After her treatment, Wharton moved Letty and the girls (and their two year old brother Peter) back to Fairhope, Alabama for the 1929-1930 school year so the girls could attend the Organic School and Letty could recuperate where admission was free to residents. After a year in Fairhope, they moved back to Paoli though the family did not have money to send the girls to private school, so they were enrolled in the local public schools. Ruth spent her senior year of high school as an intern at the Hedgerow Theatre and received her high school diploma there at the end of the year. She remained a member of the Hedgerow Theatre Company for 15 years. As a company member she appeared in shows, but also pulled her weight with chores and helping the theatre run. She drove the truck that brought audience members to and from the local train station, and was even commissary director for a while. She joined their board of directors as well, and was eventually named chairwoman.

After leaving Hedgerow in 1954, Ruth continued to work in theatre. She worked for Libby Holman for a while, whom she had met at Hedgerow, and also found employment designing lighting for a few off-Broadway shows. During this period Ruth moved to New York City and lived with Miriam Phillips in an apartment on Riverside Drive. In 1959, Ruth was traveling back to New York City by train when she met Mansfield “Bob” Bascom and his young daughter Halsey. The two immediately hit it off and spent time writing letters back and forth, getting to know each other from afar, as Bob was living in Puerto Rico and Ruth in New York. In 1962 they were married in Puerto Rico and began a life there together.

Ruth outside her home in the converted 1956 Workshop

Fast-forwarding to 1967, Ruth became an instrumental force in preparing for the future of her father’s studio and legacy. With Wharton’s health beginning to fail, Ruth began the conversation with Wharton and her siblings, Mary and Peter, about preserving the Studio and collection. Ruth and Bob were able to purchase the Studio and property, protecting it from foreclosure, and re-mortgage the property with the understanding that someday it would all be open to the public. Wharton was glad to know this was the plan for his beloved “castle on a hill” as he called it, and on May 6, 1970 he passed away.

Ruth worked tirelessly to get her father’s Studio open to the public. In December 1971, the Wharton Esherick Museum had been officially incorporated as a non-profit organization with a governing board. Ruth was elected president of the board and held that position until 1990. In 1972, in order to better devote their life to running the Museum, Bob and Ruth moved into Wharton’s Studio and began converting the 1956 Workshop (designed by Esherick and Louis Kahn) into a home, simultaneously operating the Museum and conducting tours.

Bob Bascom recalls a story from the early years of the Museum in the Tredyffrin-Easttown Historical Society’s newsletter:

“Ruth never forgot the day she was making a dress in the studio, with fabric and patterns spread out on the big desk and her sewing machine, ironing board and a litter of snippets about, when cars drove into the property, and she suddenly remembered that a group from Virginia had booked a weekday tour. Rushing outside, she warmly greeted them while I [Bob] quickly changed from my work clothes. I then hurried outside to explain to the group in detail about Wharton, his philosophies and the exterior of the studio, all the while giving Ruth quick opportunity to put away all her sewing supplies. I finally brought the group through the door of the studio just as Ruth disappeared up the spiral stair with the ironing board. Our adrenaline didn’t return to normal until late that night.”

Ruth & Mansfield (Bob) Bascom

After her retirement from the board, Ruth continued to be active with the Museum community. She attended the annual party each year and she was always available to staff to answer questions. She was an invaluable resource and always had great stories to tell about growing up at Sunekrest and exploring her father’s studio. Ruth was always quick to make a joke and equally quick to join you in laughing at it. On October 23, 2015, at the age of 93, Ruth passed away from congestive heart failure; her presence is missed by many and visitors who once had her as a guide years ago and continue to ask after her when they visit. Ruth was an incredible woman and her hard work in establishing this Museum and preserving her father’s legacy will never go unnoticed or unappreciated.

You can read more about Ruth’s life in Ruth Esherick Bascom The Extraordinary Life and Times of an Artist’s Daughter, a special publication by the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society written by her husband Bob (with Roger Thorne of TEHS), which can be purchased through the Museum’s shop or online.

Post written by Laura Heemer, Curator & Program Director.

The Dreiser – Esherick Camaraderie

Few things inspired Esherick like his closest friends, one of which was American author Theodore Dreiser. This month, we re-illuminate this friendship with an article from our Spring 1991 Quarterly Newsletter. At that time, an Esherick and Dreiser exhibit, “A Local Connection”, was on display at the People’s Light and Theater Company.

“The Dreiser-Esherick Camaraderie”

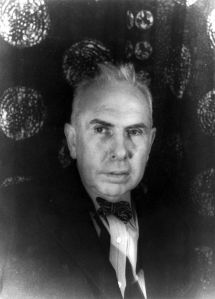

Theodore Dreiser, author of Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy, two truly American novels that broke new ground in literature, is considered one of America’s literary giants.

Dreiser and Wharton Esherick first met at the Hedgerow Theatre in 1924 when Dreiser drove over from New York to see a young woman friend perform there. Arrangements had been made for Dreiser to spend the night at Esherick’s house in Paoli. Esherick, who was seated directly behind Dreiser in the theatre, introduced himself as Dreiser’s host for the night; he was given a once over and then ignored for the rest of the evening as Dreiser concentrated his attentions on the performance and his aspiring friend. However, the two hit it off and became good friends, each respecting and enjoying the other’s genius.

Dreiser, like Ford Maddox Ford and Sherwood Anderson, prominent writers of their times, found a certain combination of solace and intellectual stimulation at the Eshericks.’ Between visits they corresponded, and they each saved the other’s letters.

Within a year after their first meeting, Esherick made a cane in snakewood for Dreiser, carving the handle with a caricature of him. In the summer of 1927 he carved two busts of Dreiser – a sketch in pine, which we have at the Studio, and a finished piece in mahogany, which he gave to Dreiser. It would have been one of the first pieces made in his new studio.

September 1st, ‘27

Dear Dreiser,

Your letter received. We expect to go to Barnegat on the 10th. Will you join us even just for a night?

I want to see the Mount Kisco place very much, I know I could help you with the material end of it, construction I mean. I am conceited enough to feel that you should see my new studio before you make any very large alterations or extensions to your place. It will be an inspiration to you.

Drive down for the night, bring your household – I want to show you the head in wood of T.D. before I exhibit it elsewhere – Someday I will take your offer for a book, at present books are not very close to me.

Many thanks.

Wharton Esherick

A few months earlier Esherick had carved a woodcut depicting Dreiser at work in his New York studio. On September 9, 1927, he wrote,

… It delights me to hear how you feel about the woodcut “Of a Great City” – I had intended to send a print to a magazine but not until you, the subject, saw it. I am sending it to Vanity Fair.

In the mid-1920s Esherick made a series of trestle tables, each a little more refined and sculptural than the last. In 1928 Dreiser commissioned one with a raised lip around the perimeter in the manner of shipboard tables.

The Eshericks spent the winter of 1929-1930 at Fairhope, Alabama, a “single-tax” community based on the economic philosophies of Henry George and a winter gathering place for artists, writers and other “free-thinkers” of the time. On January 27 Esherick wrote Dreiser,

… This is a full town, full of all kinds of isms, the philosophical kind, you know. On Sunday mornings a group of 30 or 40 meet to discuss open subjects at each other’s house. Breakfast is served and then a chatter. When they met here I opened up with the Bible (Good Samaritan passage). The crowd was surprised as it was the first time the Bible was brought into the meter. Even these intellectuals are scared. I didn’t do it for a joke either. I followed it with Anderson’s mountain girl story in Vanity Fair – a “good Samaritan” act which didn’t work out. Then the crowd tore Anderson apart as only these parlor intellects can do it, missing the point of the tale. After that I brought forth your Forum article, “What I Believe.” It was read by Judge Totten and it was grand to see them scratch and fight like chicks over a worm, not knowing what to do with it after they got it. There was one, a young actress from New York, who cut your head off with one swipe, says you say the obvious, whatever she means … She did apologize after the meeting. A young single-taxer was much impressed and the article brought from him some good honest statements. It is an interesting group if you like groups, but they seem to be trying too hard to find out how to have fun.

Esherick was encouraging Jasper Deeter at Hedgerow Theatre to produce a dramatization of Sister Carrie. On May 8, 1931, he wrote:

I would like you to see Deeter’s production of “Pinwheel” by Faragoh. A strong exciting piece of directing and so simple and economical both materially and actingly. They play it Wed. 13th … Deeter is doing some excellent things and I am anxious to see what he does with your Sister Carrie.

Although “Sister Carrie” never came to fruition, Hedgerow did perform a dramatization of An American Tragedy in 1935.

Esherick suggested that Dreiser try his hand at painting, and Dreiser, in turn, nurtured Esherick’s trial efforts in writing. Esherick wrote Dreiser September 16, 1932:

It’s good of you – encouraging to think my thoughts worth putting down on paper. I recall that time in a little Italian restaurant in lower New York when you, Helen and I sat over the last of a meal, table cleared, and you took the salt shaker and piled the white grain on the white cloth, spread it with your hand like dry sand we play with by the sea. I watched you while we talked, making patterns, designs. I said you should paint or draw pictures if for no reason but to just amuse yourself. You said, “Don’t be a fool, Esherick. I know I can’t do it; I express myself in other ways.” … If I saw a pot of golf in writing I feel I would go into it, even though I often have stated that I would never go after a living – no, after money through art. I would rather push a plow than a pen or brush for money. But – what are our rules and statements for but to be twisted in a cyclone? When does the new magazine come out? Do you need any drawings for it?

In response to a letter from Dreiser requesting an article about the building of the studio for his new magazine, Esherick wrote on October 27, 1932,

Your persistent flattery and praise has forced it out – I’m thrilled to have such a man as you believing in me. I was at the shop alone the other day working on a new stool when suddenly I went to my desk and wrote off the ‘building” article, and the very next day I get a letter from Helen asking me to write an article – What a power you are! Here I am stuck away on a lonely hill – running away from people with my few talents, trying to keep them polished. It almost seems like weakness not to stand up and fight, but yet I see it as useless to buck against the mob. Most of my effort goes into a chunk of wood. Deeter once said to me you should be happy that you are working with oak instead of people. But words, people, or oak have their qualities which must be directed…

The article was never published and Esherick abandoned hopes of finding any gold at the end of the writing rainbow. Dreiser never risked rejection in painting. But the friendship continued. On February 1, 1941, Dreiser, who by then had moved to Hollywood, wrote:

Fairest Wharton:

I’m to speak in Philadelphia for the Friends of Soviet Russia on March 5 next. My plans and obligations are a little uncertain as yet, – certain peace and civil liberties groups being after me to go here and there. Just the same, with your consent and invitation, I’d like to come out and spend a night or two. I love that place so much and you know how I feel about you…

On May 4, 1942, a year after Sherwood Anderson’s untimely death, Esherick wrote:

Dear Dreiser,

Sherwood’s memoirs are out, and I had great joy reading them. I felt as if I was walking the roads of Virginia listening and in many places I find myself telling. You didn’t know Ripshin, I wish you had, Sherwood would say often “it would be good if Teddy were here now.” I feel that if he could have edited his book he would have left the father part out, it’s been said so often by him. Anyhow it’s a sweet book. I meet many friends in it. Don’t you like how he did you?

I have a friend here, Emil Gauguin the son of Paul Gauguin the painter – he tells me Hollywood is thinking of making a movie of his father, founded as he informs me on Maugham’s Moon & Sixpence which he says is not his father.

David Loew & Levin are to do it – he is objecting & they have offered him $25,000 to assist – but he does not want his father’s life botched with a sex movie. I told him I would write you, maybe with your experience with movies you could put him on the right track to get a good biography of Gauguin. It seems to me it would make a good movie even if they did stick to the truth. What say[?]

I’m still working at woods, sculpture and furniture trying to forget this mess the world is in, hoping they all will not gang up on Russia.

How are you?

Wharton

Emil Gauguin had come to know Esherick through Pricilla Buntin, whom he married, who in the late 1930s had cataloged Esherick’s oeuvre and kept his records for the work on the Curtis Bok House.

Dreiser died on December 28, 1945, at his Hollywood home. He was 75. Esherick was 58.

For more on Dreiser and other authors in Wharton’s library check out our previous post, Wharton Esherick–Reader of Banned Books?, written by Lynne Farrington, Curator of Printed Books at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of the University of Pennsylvania.

Woodcut Wednesday Highlight: Stuffed Peacocks

Usually, our Woodcut Wednesday posts on our Facebook page consist of just a few sentences about one of the over 350 woodcut prints Esherick created during his career. However, every so often, a print has a story worth more than a few sentences – and today’s print led our staff on an amazing research treasure hunt!

The featured print this week is of a lovely prismatic peacock used as the dust cover art for the 1927 publication Stuffed Peacocks written by Emily Clark and published by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, for which Wharton produced nine woodcuts.

The featured print this week is of a lovely prismatic peacock used as the dust cover art for the 1927 publication Stuffed Peacocks written by Emily Clark and published by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, for which Wharton produced nine woodcuts.

Emily Clark (1890-1953) is best known as a writer and founding editor of Richmond, Virginia’s The Reviewer, a literary magazine that played a major role in the Southern Renaissance (1920s – 1930s). Prior to the Renaissance, southern writers tended toward themes that romanticized and glorified the Antebellum South. However, the Renaissance moved writers to themes about race, gender, identity and the burden of history in the South; themes that are still relevant today. Some of the best known Southern Renaissance authors include William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, Tennessee Williams and H.L. Menken who was a precursor to the movement. Many works by these writers line the bookshelves in Wharton’s bedroom here at the Studio. This literary movement continued to inspire 20th-century writers after it’s height in the 1920s. Perhaps the best-known work inspired by the Southern Renaissance was Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1961.

Emily Clark, Courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections.

It is not known exactly how Emily Clark met Wharton Esherick, or if they met at all. Wharton could have been hired as an illustrator through her publisher, but there is a very good chance the two met through the Centaur Book Shop when she moved with her new husband to Philadelphia in 1924. The Centaur Book Shop produced a total of three publications with Esherick illustrations with woodcuts including, Song of the Broad Axe in 1924, Yokahama Garlands in 1926, and The Song of Solomon in 1927. Wharton spent a lot of time there; it was a favored meeting place of Avant Garde writers of the time and would have certainly attracted Emily Clark. You can read more about the Centaur Shop (and press) from a past post here.

In the collection at the Museum, we have eight of the original nine blocks Wharton carved for Stuffed Peacocks. Ironically, the block we do not have is the one that inspired this post! After admiring the print of the peacock, we decided to check out the blocks themselves. When we pulled them from their storage space, we found they were kept in a solid wooden box, screwed shut and stored in a separate location from the other 300+ woodblocks in our collection.

American Railway Express shipping label.

The box holding the blocks measures 13″ long, 8″ wide and 6″ high and is joined at the corners with finger joints. Pasted to the side of the box is the original shipping label from the American Railway Express Company dated October 6, 1927. Though the label has seen better days, we could still make out who the shipping company was, that the package was prepaid, when the box was shipped and that it was headed for New York on the Pennsylvania Express, Terminal 1 via the Pennsylvania Rail Road. On the top of the box is a green address label for “Alfred A. Knopf, Publisher, 730 Fifth Ave. New York City, USA” noting that the contents were “for Stuffed Peacocks”.

The blocks for “Stuffed Peacocks”, wrapped in newspaper and packed tightly for shipping.

Opening the box was even more exciting than discovering the labels on the exterior. Inside we found a stack of folded newspapers from 1927 used to fill the space between the top of the box and the eight woodblocks below. Each block is wrapped in a section of the same newspaper and wedged in tightly so they wouldn’t shift during shipping. There were even a few wadded up sections of newspaper stuffed in around the blocks. Judging by how we found the blocks, it’s quite possible that Wharton received them back from the publisher and decided that the blocks were wrapped up safe, and so he kept them in the box and stored it away.

The treasure hunt continued when we started to read the newspapers. The papers were each the same: Volume VI of The Linotype News, a publication of the Mergenthaler Linotype Company which was founded by Ottmar Mergenthaler, inventor of the linotype printing process. The publication focused its articles on the publishing business all across the United States. A small section on the front page boasts: “As usual, this issue of The Linotype News has been composed entirely on the Linotype. The news and feature heads are Linotype set. So is the news and feature body matter. Likewise the rules, borders, dashes and other ornaments. A complete listing of the faces used appears on page four.”

Clipping announcing The Linotype Newspaper in the Fourth Estate: A Newspaper for the Makers of Newspapers

The Linotype News highlighted what different printing companies were doing, how they were using and improving the linotype process as well as other articles of note to the printing community. Making the front page headline of this volume: “Lino on N.E.A. Speical Train Comes Thru With Flying Colors”, an in-depth look at a traveling print shop inside the baggage car of the National Editorial Association’s special train through Nebraska and the Black Hills as part of their Omaha convention.

So you can see how a simple Woodcut Wednesday post on our Facebook page called for a deeper exploration and more than a few sentences about one of the prints from a book Esherick illustrated. As we often find when researching Esherick and his life, you never know what fascinating rabbit trails it will take you down!

Post written by WEM Curator & Program Director, Laura Heemer.

Block from “Stuffed Peacocks” with its newspaper wrapping.

Christmas in the Esherick Archives

Sketch from the ‘Behind the Scenes at Hedgerow’ folder labeled ‘Setting Androcles for the Camera, 1947.’

Climb the red oak spiral stairs up to Wharton Esherick’s bedroom, turn the small wood latch, open the closet door and what do you find? A treasure trove of Esherick’s sketches. Boxes upon boxes organized by theme with labels like ‘Animals’, ‘Dance’, or ‘Hedgerow’ across the front, each containing hundreds of sheets of paper. Esherick was an avid sketcher, his keen eye observing and interpreting the world around him. From his earliest days as a painter through his transition to three-dimensional work, his passion for drawing remained a constant in his studio. One can imagine him with pencil in hand as he sat in the audience at Hedgerow Theatre, on a family vacation, or alone on a Pennsylvania hillside. He drew all sorts of subjects – landscapes, portraits of friends and family, actors, dancers, circus performers, and plans for furniture and sculpture. In the drawings, we can see Esherick continually inspired by movement, while his style evolved from strict representations to quick gestural drawings. The more he came to know his subject, it seemed the fewer lines he needed to express it.

Behind the scenes, we have been hard at work cataloging the sketch collection throughout the past year. Well, “we” isn’t quite accurate. Rather, one amazing volunteer, Judy Stevenson, has been volunteering her time towards this project. Carefully assessing each individual page, noting it’s content, size, little notes scribbled in the margins, Judy is gathering and organizing any and all important information a researcher or curator might want to have at their fingertips. A perfect fit for the project, Judy is the Archivist for Longwood Gardens where she manages and catalogs Longwood’s historical archives and cultural object collections. You can imagine our delight at finding so qualified a helping hand! She has cataloged over 2,000 drawings so far, which are now searchable by the Museum staff.

Take for example a folder of sketches (now easily located!) labeled ‘Christmas 1945’. Rather than sketching decorated trees or holiday bows, Esherick was sketching the people in his life. With a few decisive marks of his pencil, Esherick captured the unique, robust personalities of the faces that surrounded him on that particular holiday season. With each portrait we can imagine a lively gathering, friends whispering, laughing, telling stories and shooting glances across at Esherick as he sketched. They are the perfect reminder to be grateful for all the wonderful and colorful characters that come through our doors – as guests eager to experience Esherick’s world and volunteers eager to share and preserve it. From all us at the Wharton Esherick Museum, we hope all your holidays are full of warmth and cheer – and maybe some sketching, too!

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.

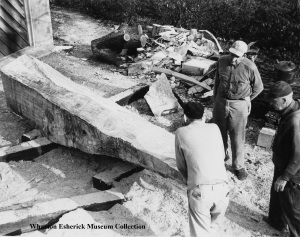

Among Wharton Esherick’s final sculptures is a pair of tall, graceful cottonwood forms known as Rhythms and Rhythms II. The latter we see here at the Museum all the time. Rhythms II stands near the center of the main gallery, its flowing curves enjoyed by many visitors over the years. The abstract form is open to interpretation (alluding to waves, water, boats, movement) though Wharton was likely inspired by the dancers that were such an important part of his life and career. Most visitors, in fact, may not realize there is a companion for this piece, Rhythms, which lives down at the South Philadelphia Free Library. Both Rhythms and Rhythms II were carved from the same large eastern cottonwood tree which was cut into two logs once it was felled by Ed Ray, Wharton’s dear friend and expert logger.

Made from the larger of the two logs, Rhythms was initiated thanks to Philadelphia’s Percent for Art Program. Established in 1959, the program requires a percentage of the cost of new buildings and development be allocated to install public art. In 1965, a percent for art meant a percent for Wharton! The new South Philadelphia Free Library board selected Wharton Esherick to create a large sculptural piece for the building’s atrium (despite the fact that when asked for at least a thumbnail sketch from the board, Wharton wryly submitting a very large sheet of paper with a sketch literally no larger than his thumbnail). The resulting piece was the over 13-foot tall cottonwood abstraction Rhythms.

By the mid-1960s, Wharton found he was a little too old to sculpt with an axe, which had always been his favorite. Instead, Wharton enlisted his two workers, Horace Hartshaw and Bill McIntyre, to help with Rhythms, carving away with chainsaws what Wharton delineated with his chalk. While his “thumbnail” joke could have ruffled a few feathers, Wharton knew the freedom his process required. He needed to be responsive to the wood and the grain, knowing his compositions could and would change as the piece came into being. Rhythms II changed as well. Initially conceived as a prismatic form, Wharton found the second log worked best with similar flowing curves.

In both sculptures Wharton captured the graceful movement of organic forms while leaving them open to interpretation, sparking the imaginations of Museum guests and library goers alike – as with one child who thought Rhythms just had to be a dinosaur’s toenail!

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.

Wharton Esherick’s Animals Move Indoors

Fall is a time of fresh air and striking foliage, and a time when nature’s critters try to find their way indoors. While keeping an eye out (and an ear out) for mice and squirrels who would like to live in Esherick’s house, this month we found ourselves recognizing all the animal faces and forms that exist in Wharton’s work. Ceramic monkeys, bronze pelicans, wooden apes – we’ve got a veritable zoo within these studio walls!

Left: “Cheeter” and “Jeeter” on display at Hedgerow Theatre c. 1935-56. Right: “Cheeter” inside the Studio today.

A few of these animal friends were initially designed for the outdoors. Cheeter, the blue horse sculpture which stands in the gallery of the studio is well known to our museum guests. Cheeter and his pal Jeeter stood outside of the Hedgerow Theatre in Rose Valley, PA from the time of their creation in 1934 until 1956 when it was determined they should be brought indoors. While Cheeter is blue now, he and Jeeter have been many colors, getting a fresh coat and fresh color as the years went on. Naturally, the pair became beloved by the neighborhood around the Hedgerow Theatre and when it came time for them to be removed, a full-size casting of Cheeter was installed at the School in Rose Valley just across the road. Children there still continue to climb up onto Cheeter’s back! Jeeter, on the other hand, made his way to Florida and is now in the collection of Modernism Museum Mount Dora.

Top: “Darling” in the woods outside the Studio. Bottom: “Darling” on display at Wharton’s 1958-59 retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts.

Cheeter and Jeeter were both made from pieces of wood brought to Wharton by his friend and wood supplier, Ed Ray. While running his logging business Ed would find sections of trees in which he could envision an animal, maybe seeing a suggestion of a leg or two, and bring it to Wharton to carve. This was the case for a sculpture entitled Darling from 1940. Darling, carved from a section of white oak, depicts an elegant and alert looking deer, something we see plenty of in the woods surrounding the Museum. Having stood out in the elements, Wharton did have to make some repairs on this sculpture (which he playfully referred to as “dental work”) replacing a rotting section of the sculpture around to nose of the deer’s face. Darling was initially exhibited outside the Hedgerow Theatre and was later among pieces featured in Wharton’s 1958 retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York City. The piece is now part of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’ collection.

Garden Horse was another wood animal sculpture to stand outside the studio. Made in 1935, only a year after Cheeter and Jeeter, Garden Horse has a simplified approach. It’s primarily vertical with broad planes to define the form, notably similar to the posts which Wharton designed for the Curtis Bok house around this same time. Unlike his companions Garden Horse was functional too – he marked the gas fill for Wharton’s kitchen stove! Spotting these sculptures in our photos and archives remind us of the fluid movement that once took place here, with sculptures coming and going, both inside and out!

The Studio in 1947, with “Garden Horse” outside marking the gas fill. Note the trees in the distance which were “topped” by Wharton to keep the valley view.

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.

Capturing the Spirit of Esherick: Memories of a Member

We hosted our Annual Members’ Party with extra fanfare this month, in celebration of our 45th anniversary as a Museum. Our program featured some wonderful speakers, who helped us take stock of our journey since 1972. Running through the event was a theme of continuity, a passing of the touch between those committed to preserving Wharton’s creation. We heard from former Director, Rob Leonard, and our current Director, Julie Gannaway. We heard from Joyce Stoeber, who has volunteered for the Museum since its inception and Lisa DiCarlo, who is new to our volunteer team this year. The afternoon was full of laughter and stories being shared both in the program and among friends. With this in mind, we found ourselves thinking about the important first-hand accounts we’ve been able to gather from those who knew Wharton Esherick, stories that enrich and breathe life into our understanding of his humor and creative spirit. One such source of anecdotes was David Wilson, who will always be remembered among the Museum’s most dedicated volunteer docents. And we don’t say that lightly! Dave was still guiding fantastic tours here at the age of 97 – sometimes giving 100 tours a year!

Dave Wilson knew Esherick from the time Wharton and Letty moved to the farmhouse in 1913. Dave was born and raised in the Great Valley. He attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts to study painting, having been inspired by Wharton’s work, and later returned to the area to run a dairy farm. His stories and memories were as invaluable then as they are now, so, in the spirit of sharing stories from past and present, we’re reposting an article from our very first newsletter (dated 1983) where Dave Wilson recounted his memories of Wharton for all to enjoy.

“Memories of a Member”

It was quite a novelty in this community to have a young artist and his bride settle here. It was real country at that time. The people were mostly farmers and were very conservative, but Wharton and Letty were soon absorbed into the community.

Having lived in the city all his life, Wharton was thrilled to be in the country. He helped his neighbors take in hay and with other such activities whenever they needed additional hands. Wharton joined the local farmer’s grange and made the scenery for one of their stage shows. Wharton often came to our house to play chess with a group of local men and during World War I my mother would invite Letty to talk to her Red Cross unit about ways of cooking to conserve food.

It was my custom as a youth to ride my horse about the Valley and surrounding hills. The back road up Diamond Rock Hill and through Esherick property was one of my favorite routes. I remember when Wharton remodeled his barn into a studio. I was particularly taken by the carvings on the supports for the little roof over the entrance, an eager Adam eyeing a coy Eve. One day, riding up their lane, I was surprised by an owl. Carved from a large hunk of wood and mounted in a hoop hanging from a tree, it was swaying in the breeze.

“An eager Adam eyeing a coy Eve” as Dave Wilson put it. These carved supports once adorned the entrance of Wharton’s barn.

Letty had an interpretive dance class – young girls dancing in thin flowing veils – that met out on the lawn at about the same hour each day. Colonel Cassat would try to time his daily horseback ride to pass the Esherick house at that particular time.

At one time Wharton had a Stanley Steamer which broke down quite often. Later, he bought a horse and a yellow two-wheeled cart. After our first real snowfall that winter, Wharton borrowed a sleigh and drove to our house for a visit. Mother invited Wharton to join us for a warming cup of coffee. “Get out of this sleigh, I should say not,” responded Wharton. Then, turning the horse sharply, as he would in his two-wheeled cart, he started off. The sleigh overturned, dumping Wharton in a snow bank.

After Wharton had made the dining table and chairs he decided that all the mid-Victorian furniture, contributed by his family, had to go to make room for his own work. The secondhand dealer had bought the lot and hauled it away – the day before Wharton’s mother came to call.

Later I married and had a farm on North Valley Road. Wharton would stop by for fresh eggs and raw milk, giving me the privilege to know him better. One day he gave me this advice for fixing up a set of old chairs I had found in the barn, “make them comfortable to your hands, round all those sharp corners and lace the seats with baling twine, which you have plenty of.”

As a dairy farmer, I always had a surplus of cow manure. One day Wharton telephoned and ordered a load of it. “Where do you want me to put it?” I asked. “I’ll leave you a sign” was his reply.

The sign Wharton left was a large wood carving of a cow’s rear end and an arrow underneath with the phrase “David Here.” The manure would be right where it belonged!

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.